Caravaggio

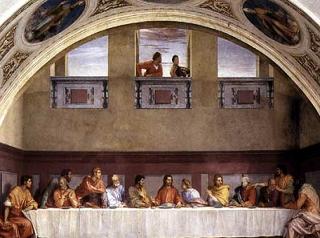

During the period 1592-98 Caravaggio's work was precise in contour, brightly colored, and sculpturesque in form, like the Mannerists, but with an added social and moral consciousness. By 1600 when he had completed his first public commission the St. Matthew paintings for the church of San Luigi dei Francesi, he had established himself as an opponent of both classicism and intellectual Mannerism. Caravaggio chose his models from the common people and set them in ordinary surroundings, yet managed to lose neither poetry nor deep spiritual feeling. His use of chiaroscuro - the contrast of light and dark to create atmosphere, drama, and emotion - was revolutionary. His light is unreal, comes from outside the painting, and creates deep relief and dark shadow. The resulting paintings are as exciting in their effect upon the senses as on the intellect.

Caravaggio's art, strangely enough, was not popular with ordinary people who saw in it a lack of reverence. It was highly appreciated by artists of his time and has become recognized through the centuries for its profoundly religious nature as well as for the new techniques that has changed the art of painting. Though Caravaggio received many commissions for religious paintings during his short life, he led a wild and bohemian existence. In 1606, after killing a man in a fight, he fled to Naples. Unfortunately, he was soon in trouble again, and so was forced to flee to Malta where, finally, after a series of precipitous adventures, died of malaria at the age of thirty-six. His influence, which was first seen in early seventeenth-century Italian art, eventually spread to France, England, Spain and the Netherlands.

Michelangelo Merisi of Caravaggio (Milan 1571 – Porto Ercole 1610), a famous and much copied painter, who had basked in the protection of cardinals and prelates, but who was also wanted by the papal guards for a homicide committed in Rome in 1606, was found dead on the beach at Porto Ercole.

This was the shabbily dressed individual with a scratched face who had wandered along the coastal road for two days screaming at the sun and cursing a ship that only he could see. Carrying only a few things, he took a boat from Naples to Rome, under the patronage of Cardinal Gonzaga who had arranged his surrender. When he landed he was taken prisoner and placed in goal, where he stayed for two days before being released. On returning to the beach he found that the ship had sailed. Furiously and desperately, he ran up and down the beach trying to get a glimpse of the ship and the things he had left on board.

After a while he was taken to bed with a high temperature, where he died, unaided, in as bad a way as he had lived.” Giovanni Baglione The life of painters, sculptors, architects and engravers.

This is the description of Caravaggio’s last days by one of his main biographers, someone who was not completely detached, as is obvious by his last venomous phrases. He had met him in the “courts of justice”, being a painter in his own right, and had initially been fascinated by him only to end up with a sincere and confessed hatred. He had, perhaps, been a competitor in the field of friendships, protection and commissions. The Abbot Giovan Pietro Bellori is in agreement with this version of the facts given by Baglione. In one of his works in 1672 he held nothing personal against Caravaggio but detested him because he was the head of the naturalistic school of painting. A third biography places Caravaggio as travelling directly from Malta to the Tyrrhenian coast. A letter to Cardinal Borghese states that “poor Caravaggio did not die in Procida but in Porto Ercole, whilst on his way by ship to Palo, where he was imprisoned and freed on payment of a large sum of money, then proceeding overland, perhaps on foot, to Porto Ercole where he fell ill and died.” There is, therefore, some doubt as to the truth of Baglione’s story but the death of the painter at Porto Ercole is as certain as the date of 18th July and the tragic events that seem a just end to a tormented life. He might have died the previous year in Naples following badly treated wounds perhaps inflicted by a group of obscure assassins, Papal or Maltese soldiers, assassinated in Porto Ercole or remained a victim of malaria.

The two days of lonely wanderings along the beach, with his brain in an already-critical condition, (one of his clients in Sicily had already defined him as a “troubled brain”), sun-burnt and deprived of his few belongings that had been left on the ship, must have added a taste of punishment to the drama, a fact that would have certainly appealed to Baglione. But why did he go to Argentario when his destination was Rome? Perhaps the announced pardon for his death penalty was not wholly official and it was more prudent to land in the Kingdom of Naples rather than in the Papal State. Even before this, why did he leave Naples where he had various well-paid commissions if not to end a life as a fugitive to avoid a death penalty, even carried out by an assassin, such as that attempted on his life when he returned from Sicily?

He also had enemies amongst the Knights of Malta. If one questions the motive for his arrest and hasty departure by ship (perhaps he had a calendar to respect) one might arrive at a hypothesis of a welldesigned trap, an organised leak of information regarding his pardon so that Caravaggio would give himself up to the Spanish guards stationed at Porto Ercole. They were ready to carry out the dirty work for others and, in this way, free pope Paolo V of the mess in which he had been placed on the insistence of his preferred nephew, Scipione Borghese, a cardinal due to parental influence and a defender of the condemned man. It is impossible to discover what happened during those two days in prison. The reason for his arrest has been attributed to mistaken identity with Caravaggio being taken for a wanted man, perhaps due to his facial wounds (“his wounds made him unrecognisable” Baglione) or according to the law which stated that a man was not free at the time of his pardon. The insistence of the biographers on the large sum of money paid to free him might cover up a much more vulgar robbery. To complicate things Caravaggio declared himself to the Spaniards as a Maltese Knight when he was no longer one and not a Spanish Knight, an honour that had only recently been given him by Phillip III.

Naples 1609-1610. One of the last paintings by Caravaggio (some people think it is the last, but this would be too significant a coincidence if it were true) is David and the Head of Goliath sent to Cardinal Borghese, his mediator with Paolo V. The young man killing the giant does not possess the usual triumphant air even if, according to classical iconography, he should represent Christ victorious. But he appears rather thoughtful and almost moved to compassion for his adversary. In the forefront stands the expressive, enormous head of Goliath with its particularly macabre dripping blood. It is, however, the head of Caravaggio for he often inserted self-portraits into his works. The wound on his forehead reminds one of the recent assault and the more evident feeling is that of a plain and strong message to the receiver of the painting after the request for a pardon.

Caravaggio is a desperate man, the open eyes of Goliath are blind because he cannot see the future and even his slayer seems perplexed. A desire for atonement may be noted, a symptom of masochism or the wish for auto-castration. This is the thesis of a strange, almost lacanian text by two American authors, “Caravaggio’s Secrets”. Another two interesting titles in English speak of Caravaggio’s Obsession, the Caravaggio Conspiracy and Caravaggio and his two Cardinals. Here the painter declares himself a dead man as well as a sinner but before asking for a divine pardon he asks for that from the pope. He wants to return to Rome, return to his environment, benefit from the rich, artistic Roman life and his pleasures, see his friends again, cardinals and non. His stay in Naples (the second for the artist) had not begun well with him being wounded in front of the Cerriglio restaurant on the 24th October 1609. Caravaggio had only been in Naples for about ten days and had found himself “ in the middle of some armed men”. He had defended himself but had remained so badly wounded that word had spread of his death. Despite his wounds he did not stay still for long and perhaps for this reason they did not ever heal completely. The paintings of this short period include the “Resurrection” for the church of St. Anne of the Lombard, destroyed in the earthquake which hit Naples in 1805, the “Annunciation” at Nancy and “Salome with the head of John the Baptist”, donated to the Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt to thank him and to make him cease the attempts to kill him or to thank him for having helped his flight from Malta. There is also the “Denial of St. Peter”, the young nude figure of St. John the Baptist and that which is surely the last work of Caravaggio, the “Martyrdom of St. Ursula”, commissioned by the Genovese nobleman, Marcantonio Doria. In these paintings the typical Caravaggion“half-bust” figures, are sometimes in the foreground as in the “Denial”, others are extremely close, captured at the moment that the arrow pierced the saint. More than suffering, the martyr seems surprised. He carries his hands to his chest and looks to see what has hit him. Behind St. Ursula appears a self-portrait of Caravaggio, intent on observing a scene where the sacredness of the myth is surrounded by an earthly realism. The way in which this humanisation of the saints and the divine and the reduction of the sacred is reconciled to the training of the Council of Trento and the Counter-reform, even when considering works of art, (Cardinal Federico Borromeo, quite orthodox in his trials against witches, wrote the De Pictura Sacra) is a widely discussed question of almost the same proportions as the religiousness or homosexuality of Caravaggio himself. There are few images of Christ, saints and martyrs with their feet off the ground in his paintings, only a few angels and this was already a choice against the mannerism and the suggestions of priests and theologians. The number of Caravaggio’s works that were refused by their purchasers because they were considered “vulgar” suspected of being heretic or at least unorthodox is considerable and might serve as a note in the tormented relationship between the artist and the institution. It should be noted that when the Church rejected some paintings, cardinals and priests ran to buy them for their private collections.

Sicily 1608-1609. Caravaggio’s brief stay in Sicily did not end in a flight as it had begun. The painter probably wanted to return to Naples where years before he had been well accepted and he intended moving one step closer to Rome, having had news of the good probability of the revocation of his conviction for the murder of Tomassoni.

Another hypothesis is that there had been threats from Malta after being given the honour of Knighthood and his rapid expulsion from the order with the consequent imprisonment and evasion.

He found an old Roman friend, colleague and model in Syracuse, Marco Minniti, who obtained commissions for him from the Senate. His first was the altar-piece of the burial place of Saint Lucia for the church dedicated to the Syracuse martyr, a canvas of 408 x 300 cm. painted in record time (he arrived half way through October and in December Caravaggio had already left for Messina). The large wall covering almost two thirds of the background of this scene is thought to show a certain tiredness on the part of the artist and judged to be a solution for the completion of the work, just like the wings of a theatre which have the effect of diminishing the actors, who appear oppressed by the sad function they are assisting. Two massive, almost daring, grave-diggers appear in the foreground and seem to step out of the canvas, re-enforcing the unity of the afflicted group whilst the establishment figures, the bishop in his robes and the soldier are protected, almost as if they are there for work. The distended body of the saint shows one of the more audacious Caravaggian traits: the distance between the shoulder and the hand is no longer than thirty centimetres. He certainly worked quickly when painting the clothes, however. Francesco Susinni wrote a century later: "his work was so well accepted that it was celebrated and copied in Messina and many other cities of the kingdom." A rich Genoese merchant in Messina, Giovanni Battista de’ Lazzari asked him to paint an altar- piece with the Madonna and the saints. Caravaggio proposed the Resurrection of Lazarus in honour of his name. According to Susinno, an earlier version of the work had been destroyed due to some criticism: "Michelangelo, with his usual impatience, attacked the painting with the dagger he always carried leaving it in shreds." The dagger reappeared whilst he was working on the second canvas, brandished by Caravaggio to convince the "porters" to continue to carry Lazarus, who in the love of realism, was an unburied body “already smelling after some days”. Lazarus had not, however, obeyed the peremptory sign of Christ and seems unwilling to return to life with one hand raised towards a skull (death as a consequence of the original sin) and the other towards the Saviour. Pages and pages of exegesis have seen the reflection of the drama of existentialism in the religiosity of Caravaggio in this painting, suspended between hope and desperation, eager to atone but sceptical of personal redemption. Mysticism apart, it is interesting to note that the self-portrait figure glances neither at Lazarus nor at Christ. The action in this painting is also faced inward, typical of his short period of “light style”. Another example may be “The rest during the flight in Egypt” 1596-7, which presents one of the few, best landscape paintings by Caravaggio.

"He never let some of his characters see the light of the sun but found the means of placing them within the darkness of a closed room" observes Bellori. This allowed Caravaggio to use illumination coming from different fonts, like spotlights enabling him to work better on the shadows. If it is true that he always intended to respect reality ("he professed himself completely obedient to the model that he never painted, which was not his but belonged to nature") it is better to dose and control the drama of the contrasts, "reducing the number of light fonts to but a few."

Other works displayed in Sicily are the "Adoration of the Shepherds or the Madonna of Childbirth", a hymn to the humility with a Maria, modest and half-lying on the straw, which counterposes the geometric block formed by the shepherds and the "Nativity" (stolen in 1962) with its conventional form which, according to some critics, possibly dates back to 1600 and is probably one of the many St. John the Baptists painted by Caravaggio in the form of a young nude man in the company of a ram. The features of the young man are strongly insular and we learn from the not always reliable Susinni that the painter gave the Master Carlo Pepe head wounds when he protested at Caravaggio’s recruiting of models for his students "to form his fantasies".

Malta 1607-1608. On the 1st December 1608 the assembly of the Knights decreed Caravaggio’s expulsion from the order to which he had been admitted for artistic merit, declaring him “membrum putridum et foetidum.” It is not necessary to know the reason for these very strong adjectives. The biographers Baglione and Bellori speak of an affront to a noble “knight of justice” or a fight. Others think that news, up till then miraculously kept a secret, of his death penalty for the murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni reached Malta. The defenders of the faith could not possibly accept any individual condemned by the Church. Perhaps something had changed in the relationship between Caravaggio and the Grand Master Alof de Wignacourt, represented in three of his works ( or four but the fourth is disputable and the first, painted in Malta, has been lost).

In the first painting the Grand Master lends his face to that of Saint Girolamo Writing; the second is the Portrait of Alof de Wignacourt in his armour accompanied by a page - boy. The presence of the page - boy is unusual in portraits of those times but de Wignacourt liked to surround himself with them according to polite customs. The third portrait is more prudently known as Portrait of a Maltese Knight and shows a particularly realistic large cross on the knight’s breast. Returning to the relationship between Caravaggio and Alof de Wignacourt, it should be remembered that he was to be the owner of Salome and the head of John the Baptist. Whilst it is absurd to imagine Caravaggio as the saint, it is possible to notice a similarity in the decapitated head and to read a request for forgiveness in the painting. The most important work in Malta again concerns an execution. It is the enormous canvas of the Beheading of St. John the Baptist, a commission obtained thanks to the Grand Master (whose coat of arms appears on the original canvas). The painting was greatly appreciated: "as well as the honour of the cross, the Grand Master hung a rich, gold chain around his neck and gave him two slaves as a gift" wrote Bellori. The detail of the thrashing and the blood which flows from the martyr’s neck particularly struck the fantasy of Maurizio Calvesi, father of all psychoanalytical iconology, who saw a polisense based on the triple significance of "segnatura" (signature, bleeding, the act of signing oneself with holy water which is also used for baptism). An illusion of the sacraments of the baptism connected with the Baptist: the dagger is identified with the aspergillum, the blow with the forgiveness and the blood with the holy water. This signature is possibly the height of Caravaggio’s Baroquism. It is disputable just how much of the Baroque there is in Caravaggio and how much there is in his commentators. With regard to an interpretative criticism of objects present in the canvas, it is perhaps better to observe the balance of light and shade, the geometry of shape, the speed of painting which indicated the importance given by the artist to one element rather than another and, perhaps, an inspection which reveals his reflections (as in the Martyrdom of Saint Matthew in 1600). It was in Malta that Caravaggio also painted Saint John at the Spring and a Sleeping Cupid, far different from the triumphant Cupids of before, a type of “imago mortis” in brown, black and grey that reveals the funereal state of mind of the painter, or the Crucifixion of St. Andrew that most place in his previous Neapolitan period.

Naples 1606-1607. The hope that had pushed Caravaggio to leave Naples and try to obtain in Malta the honour that might offer him the possibility of a pardon from Rome, had been destroyed, only to double the enemies from whom he had to flee. Even Naples had been the destination after a flight from the Papal territories. He had found hospitality here with Luigi Carafa, son of the Duke of Mondragone and Giovanna Colonna, sister of Cardinal Ascanio. Despite the "death penalty" emitted against him for the murder of Ranuccio Tomassoni, he did not lack protectors. It seems that the famous Virgin of the Rosary had been commissioned by Luigi Carafa himself for his family chapel which was dedicated to the Madonna of the Rosary, the saint that had helped his father Antonio, Duke of Mondragone win the battle of Lepanto. The altar-piece was never placed in the chapel and in 1607 it was offered for sale at 400 ducats. It is, however, difficult to imagine why the painting was not accepted. Many other works had been removed from the altars because they were judged indecorous or suspected of containing unpopular theological ideas but here everything is chaste and sacred apart from the recidivism of the dusty feet of the beggars in the forefront. We know that realism stopped Caravaggio from altering nature and it would not be the first time that dirty feet were judged improper in a sacred theme such as the Madonna of Loreto.

There is a Saint Peter martyr, worshipped as the patron of the Holy Inquisition, on one side and Saint Domenico on the other and the Madonna-Church, mediatrix of forgiveness in a dominant position, which left no suspicion at all of a tepid adhesion to the Counter-reform. Realism applied to doctrinal themes may also be found in another important work commissioned by Pio Monte, (a founder of assistance and charity), the Seven Works of Mercy. Someone wrote that the painting seems to be placed in a lively Neapolitan street, apart from the group of angels and the Virgin with Child. The decision to unite the seven representations in one scene was absolutely new and courageous in respect to the tradition that required every work of mercy in its own space. Here everything is in movement and is overlapping, proceeding in glimpses (from the dead to be buried only the feet are visible) with references to biblical themes and everyday scenes such as the visit to the prisoners interpreted by Cimone and Pero. Perhaps the model used in the Madonna of the Rosary looked too much like Pero, who shows her breast to feed Cimone and Caravaggio often used models from the streets. In the Seven Works of Misery almost all the figures are of common extract and the presence of the Madonna, this time lifted off the ground whilst she observes her Forgivers in their work, responds to a precise request of the purchaser.

Together with the altar-piece Caravaggio also produced in Naples some "easel paintings" such as David with the Head of Goliath, the Coronation of Thorns and a copy of Salome with the head of St. John the Baptist (the original was lost). Other large paintings are the Flagellation and the Crucifixion of St. Andrew which some believe to have been painted in Malta. His stay in Naples must have been a happy period for Caravaggio, heralded as an innovator, full of admirers and followers enough to influence in a determining way the passage of Neapolitan art and more modern forms. The reason for his transferral to Malta still remains a mystery and many simple hypotheses have already been put forward. However, he was forced to flee to Naples from Rome, where he had been well-received after having left his native Lombardy in 1592.

Rome 1592-1606. The idea of a similarity between the model of the Seven Works of Mercy and that of the Madonna of the Rosary stems from the habit of the artist to frequently use the same model and from the certain identity of the woman, Lena, who posed for many other paintings, and was the origin of many of Caravaggio’s problems (together with his quarrelsome character, the habit of going armed even without authorisation, the frequentation of the worst areas of Rome between one and five o’clock in the morning, to detest wholeheartedly the police and to lose no occasion to provoke them). Lena was a splendid commoner. Her job was to "stand in Piazza Navona near the doorway of the palace of Mr. Sertorio Teofilo". Others have defined her as a courtesan or a "dirty prostitute" but it is quite probably true that she posed for the contested Death of the Virgin. Only a few have suggested that she owned a small stall. Caravaggio had an argument with a notary known as Pasqualone over Lena that ended in a trial and a request for mercy and conciliation. Other actions were taken against the artist for minor quarrels, carrying arms without a licence, affronting the guards and defamation (famous is the action brought by Giovanni Baglione, his rather unkind biographer, mocked in so-called poems, where the least harsh epithet was "Giovan Coglione" or "Giovan Testicles". All these ended without serious consequences, an evident sign that Caravaggio was well protected by people high up in the Church including Cardinal Francesco Del Monte, who had offered him hospitality in his palace. The last trial for the murder of Tomassoni had a fatal outcome. Using Lena as the Madonna provoked Caravaggio infinite problems with his purchasers who refused the altar-pieces, invoking questions of orthodoxy but, basically, it was her presence alongside the novelty and naturalism of the narration. The Madonna of Loreto or the Madonna of the Pilgrims, the work chosen as a symbol of the Year2000 Jubilee, was not removed from the altar but it provoked "strong uproar" so that everyone ran to see it. We do not know what caused this but the altar-piece certainly did not respect traditional iconography with the house transported by angels that many people expected. It displayed instead a Madonna, sinuous in form, waiting at the entrance to her house for the two dusty-footed pilgrims in the foreground – tradition dictated that pilgrims walked the last steps to the sanctuary without shoes and Caravaggio faithfully represented this fact. The left foot of the Madonna raised perplexing thoughts. Was it too graceful or anatomically incorrect? Another altar -piece where Lena appeared was removed in less than a month after its placement in the Basilica of St. Peter’s, moved to another church and then offered for sale. This is the Madonna of the Snakes or Dei Palafrenieri in 1605. The baby Jesus was too naked, Mary’s breast was too visible as she bent down to watch the snake as she squashed it or was the figure of St. Anne too prominent? The work was, however, refused.

Another much discussed canvas was the Death of the Virgin, judged to be scandalous for the naked legs (really the ankles) of the Madonna, her bloated corpse and, undoubtedly, because the model had been a courtesan or worse. Once again Caravaggio had made the error of using realism, refusing the traditional idea of the “transit” of the Virgin, the sleep of Mary, in order to paint a painfully human death which refused the hope of a future after life had finished.

Caravaggio’s heresy had been a double one, both doctrinal and artistic. Voices were heard that he had not used Lena as a model but had instead used the corpse of a drowned woman. In his letter, Maurizio Calvesi disagreed with everybody and, with an injection of Baroque, decided to see the "Madonna full of Forgiveness" Not all the works that Caravaggio saw rejected had Lena as a protagonist. The Conversion of Saulo for example, was judged to be too physical or too material in the apparition of Christ, who, in the second version, disappeared in place of a blinding light. The painting of Saint Matthew and the Angel, in the copy that was lost during the last war, shows a decidedly more tempting than domesticated ephebe. In the altar –piece of 1600 for the church of Saint Luigi dei Francesi the angel descends from the heavens, at a prudent distance from the saint. Rome, at those times, was less homophobous than wanton children in Victorious Love or portraits of women of dubious reputation in the Conversion of Magdelena now testified against and discredited his morality. His last friends managed only to help him flee to Palestrina or Paliano, near Rome.

Once he had left Lazio, apart from briefly meeting the faithful Minitti in Syracuse, he had to court admirers and supporters as he had in Naples and Malta, whilst continuing his flight. Who or what persued him, considering that the death penalty for this incident could easily have been changed if someone high up had desired it, is yet to be demonstrated.

Amidst papal and Maltese aggravations, dangerous friends, private repentance and desire for atonement, there only remains to add that he died, alone and without help, at thirtynine years of age.

Visit Florence

Previous

Next

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Collina

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Periferia

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Semi-Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Semi-Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Periferia

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Periferia

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Semi-Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Ponte Vecchio

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Periferia

-

Area: Periferia

-

Area: Semi-Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Periferia

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Semi-Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Semi-Centro

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

-

Area: Centro storico

Comments